In case you missed it – Senator Dave McCormick (R-PA) sat down with Washington Post columnist Salena Zito and Senator John Fetterman (D-PA) to talk about how they can work together to create and protect jobs in Pennsylvania, support the United States’ strongest ally in the Middle East, Israel, and more. McCormick and Fetterman are one of only three bipartisan delegations in the Senate, and they are working to collaborate and deliver wins in Washington for all Pennsylvanians.

In case you missed it, the full piece is below. You can check out a bonus segment from Fox & Friends with guest Salena Zito on her conversation with McCormick and Fetterman. Follow @SenMcCormickPA on X for additional updates.

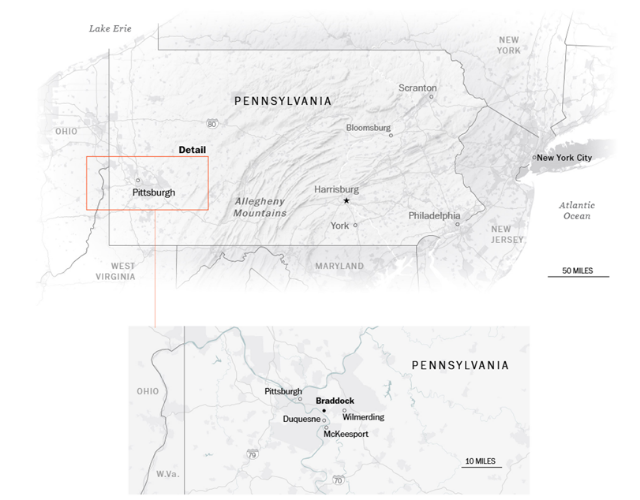

WILMERDING, Pa. — Evidence of greatness past is everywhere you look in this western Pennsylvania town, starting with the derelict Westinghouse Air Brake plant. This 300,000-square-foot factory once drew tens of thousands of immigrants and southern Blacks for good jobs and the chance to be part of something bigger than themselves. The product they made here revolutionized the railroad industry, producing air brakes that permitted trains to travel safely at higher speeds, accelerating America’s economic growth.

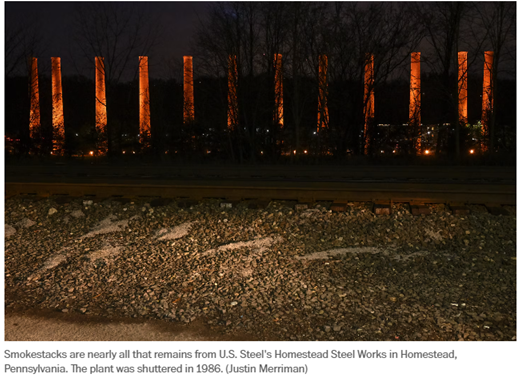

People in the Pittsburgh area of western Pennsylvania still identify — culturally, politically and economically — with that work ethos, despite the fact that the steel industry collapsed around them 40 years ago.

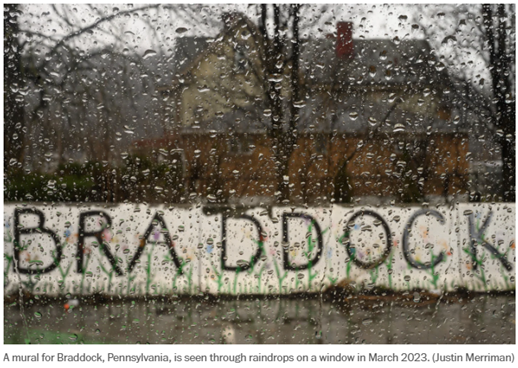

Towns such as Wilmerding, Duquesne, McKeesport and Braddock are what’s left behind. Unemployed workers followed jobs elsewhere, an exodus that emptied churches, fraternal clubs, barber shops, grocery stores and small businesses. Tight-knit families strained as sons and daughters departed.

There is a reason there are so many Steelers bars around the country: The people who moved away wanted to stay connected to the region of their childhood and heritage.

Pennsylvania’s politics can be a riddle, often defying the assumptions of national pundits. In November, the state elected a conservative, Trump-supporting military veteran and former hedge fund CEO, Dave McCormick, to be a U.S. senator. Just two years earlier, many of the same voters helped elect Sen. John Fetterman, a Democrat and a strong defender of legal marijuana who brags about his F rating from the National Rifle Association. Barack Obama won here by 10 points in 2008 and five points in 2012, followed by Donald Trump in 2016 (0.7 points), Joe Biden in 2020 (1.2 points) and Trump again in 2024 (1.7 points).

If you want to understand why, it begins here in western Pennsylvania, where manufacturing once was king, union membership coveted, and church attendance — along with a shot and a beer after Mass at the Moose Lodge — was the way of life.

Every month for the next year, I will offer Post readers insight into Pennsylvania’s culture and politics, a travelogue of sorts along the back roads of the nation’s most-populous swing state. I have covered this state for more than two decades as a reporter and have lived here for more than 65 years. Some of my ancestors first arrived here in 1632.

I’ll introduce you to the people, the culture, the economy and Pennsylvanians’ profound sense of place — most people live within 10 miles of where they grew up — and explain how those characteristics often determine our politics.

Who we are and why we vote the way we do is inextricable from the more than 41,000 miles of blue highways — state roads and old U.S. routes — that crisscross the stunningly varied geography between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Steel is literally everywhere you look: It’s not only the brand of the NFL team. Our signature beer is Iron City; the tallest building in downtown Pittsburgh is still called the U.S. Steel Tower by locals, though the company vacated it decades ago.

We begin in Braddock, as did the American steel industry, and, one could argue, the nation itself.

Beneath U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thomson Works lies Braddock’s Field, where British Gen. Edward Braddock was mortally wounded during the opening salvos of the French and Indian War, putting his young aide-de-camp, George Washington, to his first military test. Had there been no French and Indian War, there would have been no need for the British crown to tax colonists to pay down the debt incurred by winning it — and thus no need for those colonists to react with a tea party and a revolution.

What better way to examine Pennsylvania politics than through its two senators? Pennsylvania is one of only three states with senators from different parties. Yet even in today’s polarized political environment, the two men maintain a warm relationship. They know they have to collaborate to bring federal dollars home to Pennsylvania. At my request, they agreed to sit for a casual interview to get to know each other better and to discuss their common goals.

On a Sunday morning, early in February, the two senators sat down together in Fetterman’s home, a converted car dealership directly across the street from the U.S. Steel plant in Braddock. Fetterman’s three-legged pit bull immediately took to McCormick, who was dressed casually in black jeans and a down vest, jumping all over him, licking and begging for attention — which she got. Despite their different backgrounds, the men displayed an easy camaraderie.

On a Sunday morning, early in February, the two senators sat down together in Fetterman’s home, a converted car dealership directly across the street from the U.S. Steel plant in Braddock. Fetterman’s three-legged pit bull immediately took to McCormick, who was dressed casually in black jeans and a down vest, jumping all over him, licking and begging for attention — which she got. Despite their different backgrounds, the men displayed an easy camaraderie.

Their paths back to Pennsylvania, where they both grew up, are strikingly different.

Fetterman first moved to the area in 1995 during his service with AmeriCorps, where he taught high school dropouts in Braddock, a poverty-stricken town that is 75 percent Black. He left to earn a master’s degree in public policy from Harvard University, then came back in 2001 to establish a youth program in Braddock. In January 2006, he was sworn in as the town’s mayor, a part-time position that paid $150 a month. He held that job until January 2019 and took it to heart; nine tattoos on his right arm display the dates of nine violent deaths in the town while he was mayor. He then served four years as lieutenant governor before running for the Senate. He had lost in the 2016 primary but won when he tried again in 2022.

Fetterman first moved to the area in 1995 during his service with AmeriCorps, where he taught high school dropouts in Braddock, a poverty-stricken town that is 75 percent Black. He left to earn a master’s degree in public policy from Harvard University, then came back in 2001 to establish a youth program in Braddock. In January 2006, he was sworn in as the town’s mayor, a part-time position that paid $150 a month. He held that job until January 2019 and took it to heart; nine tattoos on his right arm display the dates of nine violent deaths in the town while he was mayor. He then served four years as lieutenant governor before running for the Senate. He had lost in the 2016 primary but won when he tried again in 2022.

His tattoos, shaved head, 6-foot-8 frame and habit of wearing shorts and hoodies everywhere were bound to attract attention in the Senate. But he became a focus of even more scrutiny because he won election after having suffered a debilitating stroke. Then, early in his tenure, he checked himself into Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for clinical depression and conducted his work from there. (He is an outspoken advocate for mental health care.)

Unlike many in his party, he was willing to engage with Trump and visited him at Mar-a-Lago in Florida in January. Trump called Fetterman “a fascinating man” in an interview with me right after their meeting.

Contrast that with McCormick, a West Point graduate and Gulf War veteran, who moved back to Pennsylvania in 1996 with a degree in international relations from Princeton University. He began work as a consultant for McKinsey and Co., and eventually became CEO of a Pittsburgh software company. In 2005, he was invited to join the George W. Bush administration where he worked in the Commerce and Treasury departments, which was followed by 10 years at Bridgewater Associates, a Connecticut hedge fund. Like Fetterman, he also lost his first primary race for the U.S. Senate, to Trump-endorsed Mehmet Oz in 2022. (Fetterman defeated Oz in the general election.)

McCormick ran again in 2024, this time challenging Democratic incumbent Bob Casey. McCormick’s message throughout the campaign focused on bread-and-butter issues such as inflation, opening up the state’s natural gas supply, and immigration.

Fetterman and McCormick have much in common. They are both die-hard Steelers fans and devotees of Pennsylvania-based Sheetz convenience stores. Both grew up on the other side of the Allegheny Mountains, less than 100 miles from one another: McCormick in Bloomsburg, Fetterman in York.

Sitting on an oversize brown leather couch, the senators compared notes on their favorite outdoor places in Pennsylvania, mentioning Erie’s Presque Isle State Park and the town of Jim Thorpe. They animatedly discussed the state’s importance as one of the nation’s top suppliers of eggs, maple syrup and snack foods. Fetterman particularly lauded the potato chips. “There should be a law that they all use tallow,” he said. McCormick leaned in: “You know, we could do a cosponsorship on a bill for that.”

Sitting on an oversize brown leather couch, the senators compared notes on their favorite outdoor places in Pennsylvania, mentioning Erie’s Presque Isle State Park and the town of Jim Thorpe. They animatedly discussed the state’s importance as one of the nation’s top suppliers of eggs, maple syrup and snack foods. Fetterman particularly lauded the potato chips. “There should be a law that they all use tallow,” he said. McCormick leaned in: “You know, we could do a cosponsorship on a bill for that.”

The conversation was organic, straightforward and reflected two guys finding common ground. In many ways, it mirrored conversations I have witnessed for years in Pennsylvania diners, bars, bowling alleys, community centers, Elks clubs and Farm Bureau meetings — conversations between people whose lives and interests and politics defy conventional stereotypes.

The first time McCormick and Fetterman met was in October 2023, at a service marking the fifth anniversary of the Tree of Life synagogue massacre in Pittsburgh, when 11 worshipers were murdered in what is believed to be the deadliest act of antisemitism in U.S. history. At the time of their introduction, McCormick was running against Casey, Fetterman’s Democratic Senate colleague.

McCormick and his wife, Dina Powell McCormick, approached Fetterman. “It was somber, just given the anniversary, and they introduced themselves, and they were very pleasant, and I was just like, ‘Hey, I know it’s going to probably get hairy, but always going to keep everything above the belt,” Fetterman recalled. McCormick smiled: “I think he said, ‘It might get a little spicy.’”

Indeed, Fetterman campaigned for Casey, who had become a friend as well as a colleague. The race was so tight it went to an automatic recount. McCormick won by 0.22 points. At the time, Fetterman remarked: “This hits me.”

Still, Fetterman would have to work with his fellow senator. After the election, they met with their wives for an informal dinner at a Brazilian steak house in downtown Pittsburgh. “He is much more recognizable than me, so the people were lining up to get a photo with him” McCormick said. “At one point, I think John felt bad and finally pointed to me and said ‘Hey, he’s a senator, too.’” McCormick points to that December dinner as the moment they both understood they could work together for what was best for the state.

“We’re going to agree on many things, we’re going to disagree on some things,” Fetterman said. “And it’s never going to be about just trying to create needless drama. I don’t anticipate that ever happening.”

McCormick said that, in the days following Hamas’s Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel, he watched as Fetterman spoke out on camera and on social media in support of Israel — despite many in his own party expressing a stridently different worldview.

“He did it with such clarity and forcefulness, and the things he was saying were so identical to the things I was saying that people started asking me what I thought of him,” McCormick said. Even though he was in the middle of a campaign, his answer always was, “Well, I know at least on this issue — and probably some others — we agree.”

Fetterman had already picked up on the rightward shift in his state and warned his party that Trump could reclaim Pennsylvania in 2024. He could sense voters’ frustration with the status quo and predicted the race would be won in the rural counties. “I fundamentally believe that whoever can carry their argument and win Erie will win Pennsylvania,” Fetterman said in August.

Fetterman had already picked up on the rightward shift in his state and warned his party that Trump could reclaim Pennsylvania in 2024. He could sense voters’ frustration with the status quo and predicted the race would be won in the rural counties. “I fundamentally believe that whoever can carry their argument and win Erie will win Pennsylvania,” Fetterman said in August.

He was right. The Democratic ticket didn’t have answers for voters hoping to see a revival of industry in Pennsylvania. Too much was up in the air. Japan’s Nippon Steel was interested in acquiring U.S. Steel, something opposed by the United Steelworkers union. Pennsylvania has massive reserves of gas but Biden as president had imposed a ban on the export of liquefied natural gas, and candidate Kamala Harris gave no indication she would lift it. Trump has already done so.

Today, the state’s two senators seem open to each other’s ideas. I watched Fetterman throw one out in real time: He told McCormick about a covid-era state Senate bill regarding the Whole-Home Repairs program, which provides grants to homeowners who need to repair their properties to keep them livable.

“No matter if you’re in Philadelphia or you’re in Cambria County, if you want to help people stay in their home, especially the elderly, and they need help with a new roof or rewiring, the legislation allows them to stay in their homes,” Fetterman explained.

Why not do the same at the federal level? “I have a couple co-sponsors, and I was about to bring it to my colleague here,” Fetterman said. “I would like to think that’s one of the things that we could work on together. … I think we can both agree that we have a housing issue here in our nation.”

Why not do the same at the federal level? “I have a couple co-sponsors, and I was about to bring it to my colleague here,” Fetterman said. “I would like to think that’s one of the things that we could work on together. … I think we can both agree that we have a housing issue here in our nation.”

McCormick responded positively. “That’s exactly the kind of thing that I love to work on,” he said. “I’m on the Banking Committee, and we had hearings last week, and the whole focus was on affordable housing. It was a huge issue in Pennsylvania, so this legislation is certainly something that I’d want to look at.”

Fetterman beamed, then turned his attention to his pit bull, still slobbering over their visitor. “I’m discovering that my dog might like him more than me,” he said. “You’re killing me,” he told the dog. “I don’t know, maybe you’re a Republican, too?”

Fetterman beamed, then turned his attention to his pit bull, still slobbering over their visitor. “I’m discovering that my dog might like him more than me,” he said. “You’re killing me,” he told the dog. “I don’t know, maybe you’re a Republican, too?”

Later, the two men walked up the ramp left over from when the building was a car dealership. From the roof, they looked down on the massive U.S. Steel plant, a fixture in Braddock since Andrew Carnegie built it in 1875. Steam poured from the stacks and the hum of machines and men working filled the air. “I want to preserve the people here’s way of life,” Fetterman said. McCormick nodded in agreement.

The future of the company is in doubt since Biden blocked Nippon Steel’s purchase of U.S. Steel on the grounds of national security. But the company is in trouble, and has said it would shut down plants and lay off workers without an infusion of capital. The idea of such an iconic American company in foreign hands seems repugnant to people on all sides of the political spectrum. Trump has said he wouldn’t object to Nippon taking a minority interest in the company but would block an all-out acquisition.

Outside Fetterman’s window, the long-long-short-long whistle used as a warning for approaching trains echoed through the valley as an engine made its way toward the plant. The fate of the company, its workers and their way of life — as well as the future of the two men who hope to protect it — hangs in the balance.

We’ll be watching.

In case you missed it – Senator Dave McCormick (R-PA) sat down with Washington Post columnist Salena Zito and Senator John Fetterman (D-PA) to talk about how they can work together to create and protect jobs in Pennsylvania, support the United States’ strongest ally in the Middle East, Israel, and more. McCormick and Fetterman are one of only three bipartisan delegations in the Senate, and they are working to collaborate and deliver wins in Washington for all Pennsylvanians.

In case you missed it, the full piece is below. You can check out a bonus segment from Fox & Friends with guest Salena Zito on her conversation with McCormick and Fetterman. Follow @SenMcCormickPA on X for additional updates.